Deadspin, a popular sports news site, has a bone to pick with FanSided, a much less popular sports news site.

The source of the spat is that FanSided (which Deadspin calls “Sports Illustrated’s Slimy Appendage” and “SI’s Grubbly Little Sibling”) pays writers a Dickensian wage. We’re talking 30 hours a week to make $50 a month—even less, in some cases.

As Deadspin tells it, FanSided is merely a “content machine” that produces SEO-driven traffic to drive up ad sales without focusing on giving readers anything of value. They took a similar stance against Vox Media’s SB Nation, another sports site, which, according to Deadspin, pays as little as $3 per blog post.

So why does Deadspin care so much?

I like to think their primary intention is to call out the injustices taking place within its trade. But let’s entertain the possibility of an ulterior motive.

Sports Illustrated, SB Nation and FanSided technically compete with Deadspin for readership (and ad placement). They pay wages that Deadspin, whose editorial staff is unionized, rightly finds unsavory. And so, Deadspin, acting nobly but also shrewdly, seized an opportunity to differentiate its values through writing.

If it sounds a bit like content marketing, it is—and a damned fine example of it. Univision was looking for a buyer of the Gizmodo Group when this all went down (which Deadspin is a part of). Obviously we can only speculate here, but what better way to garnish a brand for sale than elevate it above competitors with solid journalism?

This may be a classic case of owned media (content created in house) leading to earned media (basically, good publicity) for a brand. Just look at this headline from Boston.com:

What does this have to do with content mills?

Deadspin’s flash of content marketing genius (inadvertent or otherwise) is a good reminder that content is most powerful when it’s authentic, and content mills are anything but.

They create content for the sake of content. There’s usually some commercial case for why articles are necessary, but little regard for craft, quality and real SEO value, let alone efficacy as part of a sales funnel.

FanSided isn’t a content mill in the traditional sense since it’s publishing on its own site. But here’s how Deadspin’s Laura Wagner described the business model: “Sell ads against the inessential work produced by exploited labor.”

In other words, the priority is having words on a page act as containers for ads. Or in the case of content mills, creating filler for a company blog that’s just “good enough.”

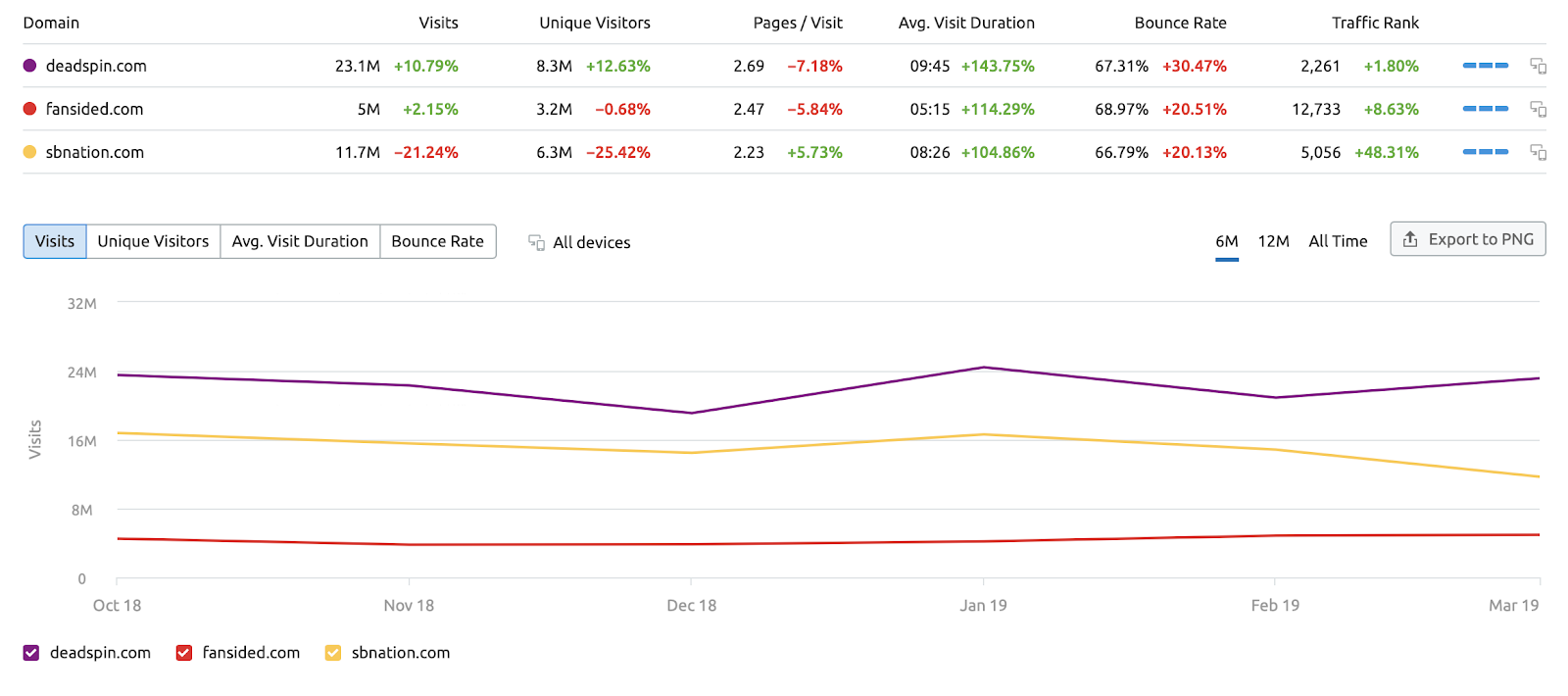

The problem is that this doesn’t work—not for brands paying content mills and apparently not for FanSided. I say this as someone who much prefers Deadspin, but also objectively:

Deadspin had more unique visitors, more pages per visit and longer average visit duration than each of its competitors. And if that wasn’t enough, it has more total visits than both of them combined.

Call it a win for high-quality content.

So wait: What exactly is a content mill?

“Content mill” is a dig at services that pay freelance content writers cheap wages to churn out keyword-laden copy for “SEO purposes.” The blog posts (and they almost always are blog posts) are not results-driven, and they focus more on volume than substance.

Examples include freelance writing sites such as Fivver, Freelance.com, Scripted, Crowd Content and UpWork.

No one markets themselves as a content mill, or by their other ignoble moniker, “content farm” for fairly obvious reasons.

Content mills have various working models. Some staff in-house editors to distribute assignments to a team of poorly compensated, remote freelance writers (they earn as low as a few bucks per article in some cases—less in FanSided’s case apparently).

Alternatively, a client might submit a pool of assignments through an online platform, which is then made accessible to writers to choose from or, in some cases, bid on. In the latter scenario, each writer can propose an amount per project, a process that can easily devolve into a race to the bottom.

Other content mills will try to get away with calling themselves agencies by generating a list of keywords loosely tied to the client brand, and then freelancing as many articles for those keywords as possible. Another common tactic is rehashing news articles and stuffing key phrases into them every 50 words or so.

You may find some content mills that accomodate a round of revisions, but a lot of them won’t. When you pay writers a few cents per word or less, you can only expect so much back and forth.

There typically isn’t much repartee between the writer and the client regarding assignments, and freelancers tend to be less privy to commercial objectives. Each blog post is just another of many low-paying writing gigs to pound out as quickly as possible.

As for the SEO value of this? There is none. Writing a blog post that ranks for a keyword is difficult, and ranking on the first page for that term is even harder. It requires careful analysis of a keyword’s relevance to what your audience is actually looking for, followed by an evaluation of the content that’s ranking for that keyword.

Fat chance you’ll find that in a content mill.

So why do companies hire content mills?

Despite the lopsided pros and cons list, many brands can’t see past the volume they get for the cost, and the promise of “hands off” service. Alternatives—hiring a writer in-house or paying an actual content marketing agency that strategizes and creates great written and visual content—demand more money, time and attention.

What some companies fail to realize (or choose to ignore) is that bad content is useless.

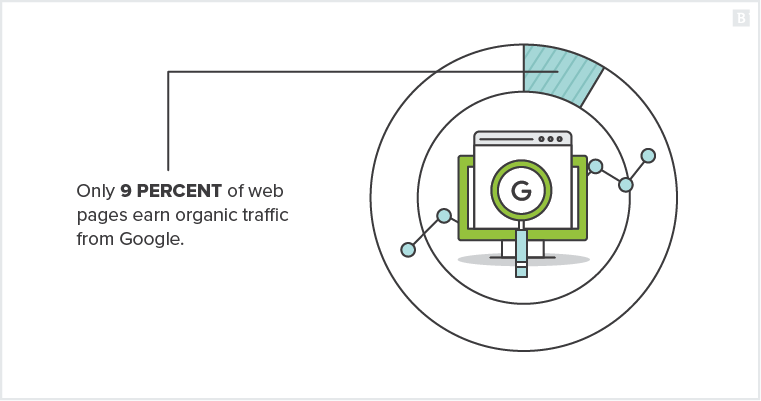

Only 9 percent of web pages earn organic traffic from Google. The other 91 percent of the internet has never been accessed via the world’s largest search engine.

With those odds, how could anyone think a blog summarizing the latest Reuters article will be among the top 9 percent?

And even if gets there, how do you ensure the people who see it are even remotely qualified leads?

The truth is, content marketing is really, really hard

You can’t game Google with some magic combination of words and phrases, and you certainly can’t do it with a cascade of overly general blog content that’s already been written 1,000 times somewhere else.

We’re talking about a search engine parented by one of the most profitable, powerful, data-affluent enterprises in the known universe, that is pouring resources into showing web users content they care about.

It’s gonna take more than a few cents per word to move the needle here.

So what should you do instead?

For one, you need to shed the subtle, unspoken and subconscious idea that you’re engaging in some form of deception. Content marketing must be a deliberate and dedicated effort to create something people actually care about, and that they can’t already get somewhere else.

Be the Deadspin of your industry.

Secondly, if you’re asking whether or not your content is good enough for Google, then you’re asking the wrong question.

You write for humans, and you optimize for Google. It’s why we always say “know your audience.”

Thirdly, you need to track the performance of your content (page visits, average page per session, bounce rate, pages per visit, newsletter signups, etc.) to deduce what’s working and why it’s working. Pivot accordingly.

Content mills aren’t designed to do any of this. The model is constructed to run up its own profit margins with low overhead, cheap labor and a valueless product.

Here’s how one self-proclaimed content-mill writer explained the job requirements:

“Most content mills don’t require professional writing experience. What matters is the ability to produce a grammatically correct writing sample that clearly communicates factual information.”

If that doesn’t put you off content mills, the ethical egregiousness of it might.

Content mills frequently underpay fledgling scribes who have yet to ascertain the full value of their writing skills. Furthermore, these mills exploit unknowledgeable organizations.

Many businesses intuitively know they need content without fully understanding what type, how to optimize it for search engines and where it fits in a bigger marketing strategy. The knee-jerk reaction is to delegate work to the lowest bidder, e.g., someone who can “produce a grammatically correct writing sample that clearly communicates factual information.”

The problem is that more than 1 billion pages exist on the web and, every day, millions of new blog posts are published. Dumping high volumes of passable content into the world isn’t going to work, and can even harm domain authority (especially if you’re keyword stuffing).

Donating money to charity is a much better use of company funds.

A defunct and dying practice

The content mill is the appendix of the marketing world—at best it does nothing. At worst, it’s a real pain in your side.

So what are the origins of this vestigial organ, and why has it stuck around?

In the late 2000s and early 2010s, brands were busy bulking up on content. Google’s algorithms were coarse by today’s standards. Volume plays and keyword stuffing were considered best practices, and they worked!

There was even a time when Brafton’s service primarily consisted of 40 200-word blog posts per month. That’s what brands needed to differentiate themselves to search engines in 2010 (but we still staffed writers, designers, content strategists and social media managers in house, all of whom received computers to work on, health benefits, paid time off, etc.).

In those days, writing jobs were plentiful, and low standards justified awful pay.

But now there’s a lot more content on the web, and Google is much better at understanding searcher intent—that is, realizing what type of content a user is actually looking for.

Search engine ranking signals have diversified to include mobile friendliness, page speed, metatags, outbound link quality, HTML errors, URL strength, SSL certification and hundreds of other factors. Too many businesses sign up for content-writing services without entertaining the possibility that their site is technically flawed.

Then there’s the strategic, non-SEO aspects of modern content marketing: What do you do to further engage someone who visits your site, and how do you do it without annoying them? The web is full of fun distractions that pull users away from your blog posts and kill the customer journey at conception.

Lamentably, none of this matters to a content mill. They get money and you get crap content.

The silver lining is that online writing services and content writing platforms of yore are slowly but surely dying off, and those that wish to endure are rebranding with agency-forward messaging, something Brafton did from day one.

Brands are beginning to understand the value of partnering with an agency content writer who is privy to clients’ strategic objectives, and works alongside project managers, consultants, content strategists, marketing directors and designers.

And this is good news for brands that want to do content marketing right.

Content marketing at a crossroads

Most of the content on the web sucks because it’s been allowed to suck for a long time.

But Google’s evolution, and the general advancement of AI and machine learning, has forced us to be better. Think about it: Copywriting for TV is broadly viewed as a respectable, well-paying industry because the medium has historically been carefully curated.

Search engines are really just massive digital curators, and they’re becoming more precise and careful in their work. And so must content creators.

The brands practicing content marketing—and the agencies such as Brafton that serve them—are at an important phase of development.

They can be FanSided, or they can be Deadspin.