Human beings love predictions.

We love to make predictions. We love to read about predictions.

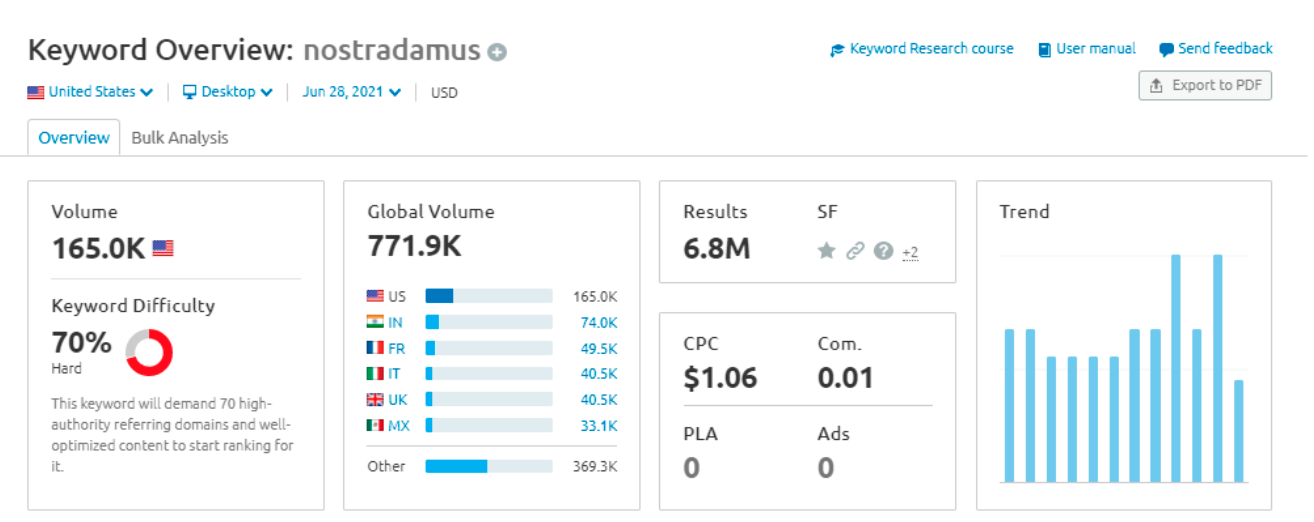

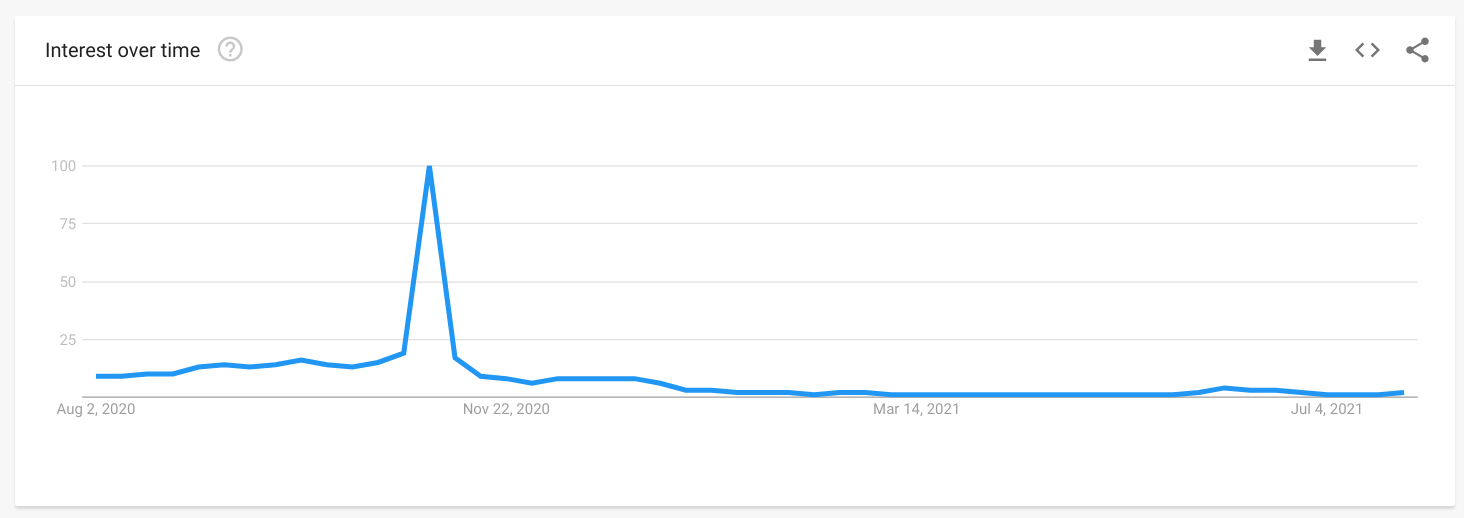

This chap Nostrodamus made a few predictions 500 years ago and he’s been trading off them ever since.

Come December, digital marketing blogs (even ours) will be offering another round of predictions for the year ahead. Many of these predictions will be intelligent and insightful.

But who wants to read a blog post about how great other blog posts are?

Instead let’s focus on some predictions (my own) that didn’t end up happening and have a good old moan about predictions posts in general.

And if you’re still not convinced, I’ve also got lots of Ghostbusters GIFs.

Subscribe to

The Content Marketer

Get weekly insights, advice and opinions about all things digital marketing.

Thank you for subscribing to The Content Marketer!

What’s the Problem With Predictions Posts?

When it comes to what’s wrong with the world, predictions posts (particularly in digital marketing) are pretty low down on the list.

But when you’ve worked in this industry for a while—reading blogs and subscribing to newsletters—you start to notice some recurring themes with predictions posts. In my experience, they fall into 3 categories:

No. 1. Self-serving Predictions

OK, so nobody is using digital marketing predictions to impress women who otherwise wouldn’t give them a second look. Or to give gullible dorks electric shocks.

But authors are often motivated by self interest.

And, yes, I know blog content is created to win traffic, build brand awareness and capture leads. We don’t just write for the good of humanity.

But oftentimes predictions posts are just an excuse to talk up whatever product or tactic the author’s agency is trying to push.

You want to know what will impact marketing KPIs next year? This thing we sell!!

In my opinion, the better predictions posts are based on real data. Anonymised survey results remove the incentive to push your own agenda. And while there’s nothing wrong believing in your products, you should know if you’re reading a prediction or an ad.

No. 2. Vague Predictions

If you’re contributing to a predictions post and your name is going to be on it you have three options: 1) promote your own products (we’ve just covered that); 2) try to sound smart (we’ll get to that when we do my predictions that never happened); or 3) play it safe.

Those risk averse predictors among us need not worry. Here’s the big, open secret when it comes to predictions posts: nobody checks to see if you were right.

But that won’t stop some of the authors of this year’s digital marketing predictions posts betting their reputations on mobile being increasingly important in search, bad UX hurting your conversions and quality content driving better rankings.

Better start adjusting your strategies now 😉

No. 3. Reheated Predictions

When the marketing team first asked me to write something for the blog, I immediately saw my chance to complain about how nobody uses source material properly anymore.

But my colleague Molly nailed that topic 9 months ago (although no Ghostbusters GIFs, which would have made her argument even more compelling).

If you’re looking for examples of reheated, rehashed content then your annual serving of predictions posts is an excellent place to start.

And we’re not talking here about taking the time and effort to go round 10 genuine digital marketing experts to see what predictions they’ve blogged or tweeted about. We’re talking about Googling “digital marketing predictions” and making your own list from whatever you find on the first page of results.

The internet is brimming with content that offers no value-add and no original ideas. There are so many posts lazily linking to wherever the author first saw the information (don’t bother to check where it originally came from, how old it is, whether it’s wrong or out of context) that eventually these posts will all link to each other and the internet will collapse in on itself.

My Digital Marketing Predictions That Never Happened

The problem with ranty blog posts like this one is that they come across all holier than thou. You feel like the author has had more fun writing it than you’re having reading it. And after a while, you’re sick of getting preached at.

So if it’s not too late, let’s try to fix that by looking at some predictions I made myself in the past that never happened (or didn’t happen yet. We have another five centuries, if Nostradamus is the benchmark here).

1. Author Rank

I wasn’t alone in predicting that Author Rank would be a thing.

When we do SEO research for clients today, Domain Authority is one of the key inputs. We want to know how our client’s site stacks up against the competition. Moz’s Domain Authority is (in my opinion) the best indicator of a site’s standing in organic search.

So if the site where you publish content influences where it ranks, why not who wrote it?

If Brian Dean had written this post, it ought to rank better in search because what he thinks about digital marketing matters more than what I think.

And while that happens in a roundabout way (his site has a stronger Domain Authority, he has a much bigger social media presence and a larger email list for promoting his articles), there is no direct link between who has written a post and how it ranks in search.

Back in 2013, I was convinced this would change. Google had just launched its own social media network, Google+, which offered, among other things, a way to author content.

We had some early success in Australia getting blogs to rank better if they had an official Google+ author. And Eric Schmidt, then Google CEO, said that while it might not necessarily be Google+, authorship would likely become a ranking factor.

“Within search results, information tied to verified online profiles will be ranked higher than content without such verification, which will result in most users naturally clicking on the top (verified) results. The true cost of remaining anonymous, then, might be irrelevance.” (Eric Schmidt, The New Digital Age, 2013)

But almost a decade later, we’re still waiting. Google+ has come and gone and at the time of writing there is no such thing as Author Rank (at least in the context of Google’s core search algorithm).

2. Knowledge Based Trust

I said earlier in this post that digital marketing predictions are often motivated by wanting to sound clever.

That was certainly the case with my Knowledge Based Trust prediction.

In 2014, I was researching a speaking slot at a New Zealand Marketing Association event when I happened upon this research paper.

The topic of my talk was the future of SEO and when I read that paper, I decided Knowledge Based Trust and the Knowledge Vault would be just what I needed to blow my audience away.

The idea that Google could figure out if content was accurate was very exciting for me as I’ve had those hang-ups about using proper source material for some time now (see mini-rant above).

And while there is no doubt that trust is baked into search signals, such as inbound links, the buzz around Knowledge Based Trust as the future of SEO fizzled out pretty quickly. Google the topic now and the most recent article is from 2015.

3. End of Keywords

A phenomenon all digital marketers will be familiar with is the ripple effect of big algorithm changes.

When Google announces a core algorithm update, it will usually put out some information about what it hopes to achieve (promote better content, downgrade spam, improve user experience etc). But how content creators and SEOs should respond is left to the community to figure out.

Sometimes this results in new “flavour of the month” digital strategies. The reaction to Hummingbird in 2013 is a great example.

Hummingbird was about speed and accuracy. The idea was that post-Hummingbird, Google would use whole search phrases rather than a few important words to determine searcher intent.

The big takeaway for marketers was that because search queries posed as questions were on the rise (wider use of voice search, users trusting Google to figure out what they wanted from natural speech), Q&A content—and lots of it—was the new holy grail.

Like the Google+ Author Rank fad, we saw some really good results from switching up blogging strategies to focus on answering as many questions as possible on clients’ core topics. We found that smaller pages, lower down the site’s hierarchy (like blogs) were starting to outperform bigger, higher profile pages that provided a weaker match to the target query.

This would surely mean the end of keywords.

Google could now figure out searcher intent. Its spiders would scuttle away and return with pages that didn’t use any of the same words in your query because it now understood what you wanted better than you did.

Not quite.

If anything, writing for search—at least how we do it—has never been more keyword-focused. Creating content to rank for one specific key phrase is how we built organic traffic to our UK website worth $100,000 per month.

But while Hummingbird didn’t mean the end of keywords, you could argue that it was the start of the shift towards topic depth as an effective tactic for ranking in search.

Google wants to return the best result for every search query. If content creators can figure out the topics most commonly associated with that query and produce a piece of content that covers those topics in greater depth, they have an excellent chance of achieving better rankings and more search traffic.

Takeaways

I’ve done everything in 3s in this post, so here is a concluding trivector for anyone still reading:

- Predictions posts – even when they’re badly disguised ads or full of other people’s ideas—are not the world’s greatest evil. Most of them are a total waste of cloud storage, but that goes for 90% of blog posts, whatever the topic.

- If you write your own predictions posts, I’d love to see some original data. Ping round an all-company email, canvas your clients, promote a 5-question survey on Instagram. Content with real original research gets lots of more links and traffic.

- And, of course, watch Ghostbusters. It’s a classic.